La Introducción

CLIENT: Glottoverse

DEPLOYMENT: In development

PLATFORM: In development

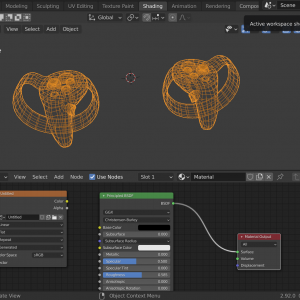

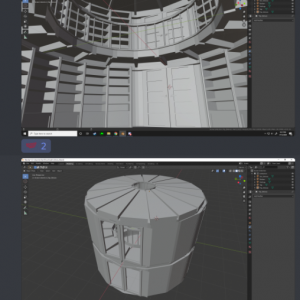

PROGRAMS: Unity3D, Blender, VisualStudio, Audacity, Maya, Substance Painter

OBJECTIVE: Create an introductory-level application as proof of concept, accessible to any user with little or no prior Spanish experience or skill, aimed at Steam and Oculus virtual stores for individual customer use.

CONCEPT: Teach users Spanish in a Virtual Reality Application using Comprehensible Input and measuring comprehension by distinct environmental player reactions.

La Introducción Game Demo

synopsis

The game was originally crafted by answering the question “what would be the most ideal classroom for a language learner?” Some schools construct their buildings so as to accommodate their learners, such as schools for the deaf making their doors glass since students couldn’t hear people on the other side of the door. The ideal classroom for a language learner is one that could change depending on the type of language which was being taught

(a library, a market, a house, a kitchen, a public square, etc.). Since it’s impossible to constantly modify a brick-and-mortar classroom, and since holodecks don’t exist yet, Virtual Reality provides a great setting to constantly modify a setting for a language learner. This way they can be provided rich and targeted language input that is relevant to their surroundings, and relevant to direct objectives.

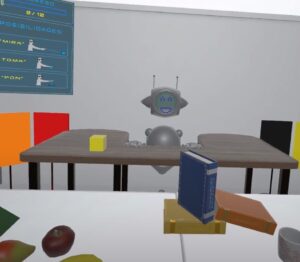

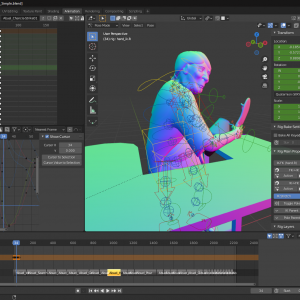

Real-time Reactive Animations

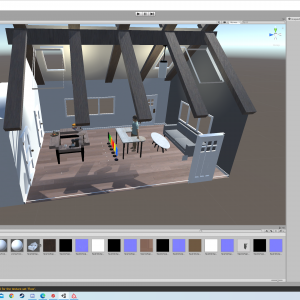

Immersive Environments

Voice Lines Recorded In-House

Interactive Learning Explained

If one wishes to teach an infant how to speak their own mother-tongue, one would never put a giant textbook filled with vocabulary and images in front of them. At face value, most everyone understands that a traditional approach to language instruction doesn’t make sense. Vocabulary lists and grammar charts are difficult, boring, and don’t provide lasting knowledge of a language. If proof is needed, one need only ask the average 40 year old what they remember from high school.

If one wishes to teach an infant how to speak their own mother-tongue, one would never put a giant textbook filled with vocabulary and images in front of them. At face value, most everyone understands that a traditional approach to language instruction doesn’t make sense. Vocabulary lists and grammar charts are difficult, boring, and don’t provide lasting knowledge of a language. If proof is needed, one need only ask the average 40 year old what they remember from high school.

The difficulty in responding to traditional classroom instruction is coming up with something else that everyone finds agreeable, and that’s not easy to do, especially when linguists and teachers who grew up with traditional instruction don’t want to leave it behind. There have been some pretty good ideas, however. In 1985 Stephen Krashen crafted the Input Hypothesis, a chart which attempted to explain how language is learned. This chart, and other models which followed in the later years of this field, all respectfully avoid one central question: what are the actual mechanisms and processes within the human mind that are responsible for language acquisition? By avoiding this question, researchers only have a couple of variables to observe: what goes into the mind, and what comes out. Very quickly, one sees that what comes out is only a by-product of what is already learned, meaning one should only focus on what goes in. Spoiler alert: vocab lists, grammar charts, and rote memorization do not lead to language coming out the other side.

By providing a lan guage learner, or a child, with basic, concrete (that is, real-world) ideas, with clear word forms attached, the mind is able to receive them and make sense of them. Furthermore, when these ideas are attached to some need or objective (acquiring food, playing a game, accomplishing a normal daily routine) then attention is drawn away from the language and is focused on the task. Counterintuitively, instead of focusing on a task resulting in a lack of language knowledge, it boosts language knowledge because the student has received that knowledge more passively. Think about it: at any point in reading this has the reader contemplated whether I used the second person singular or the third person impersonal? Language use is primarily subconscious, and it is actually counterintuitive to draw explicit attention to the acquisition process.

guage learner, or a child, with basic, concrete (that is, real-world) ideas, with clear word forms attached, the mind is able to receive them and make sense of them. Furthermore, when these ideas are attached to some need or objective (acquiring food, playing a game, accomplishing a normal daily routine) then attention is drawn away from the language and is focused on the task. Counterintuitively, instead of focusing on a task resulting in a lack of language knowledge, it boosts language knowledge because the student has received that knowledge more passively. Think about it: at any point in reading this has the reader contemplated whether I used the second person singular or the third person impersonal? Language use is primarily subconscious, and it is actually counterintuitive to draw explicit attention to the acquisition process.

Explicit attention to language detail only works when a learner has a full robust knowledge of a language. This is why children begin school at age 5 in the United States – their language knowledge and ability is already fully ripe at that time. For this video game, then, trying to teach users a new language, everything is implicit, just like it would be for a child. Thanks to the technology of Virtual Reality, as well, it is possible to simulate the real world tasks that help disguise new language exposure and help embed language acquisition that are far more natural than language taught in a classroom, even one that is focused on providing appropriate Krashen-style input for their students.

Comprehensible Input in a Classroom Setting: http://teachingcomprehensibly.com/tci-introduction/

Our Process

Our first title, La Introducción (the introduction) assumes no prior language experience. As with any new experience, the assumption is that the process will be a little overwhelming, but there are tools in place to help ease the player into the game.

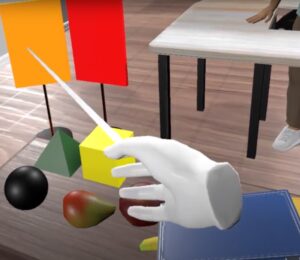

In each level, there are a number of interactions that the player is expected to accomplish in the virtual setting. Prior to each level, the player is not expected to know or understand anything about what is occurring.

First, the player will hear their instruction for the first time. For all intents and purposes it may be complete nonsense, but the player hears the novel sounds and is given an opportunity to try and process them. Then the player hears the instruction again and is directed in the virtual space to what items they should interact with. The first time the player experiences each level, there may be very little that they understand, but as they repeat the level and become more focused on listening to their instructor, they will start to remember some of the words they are being exposed to.

Each level presents ascending difficulties within itself. One version of the level provides hints to help the player accomplish the game, as described above. The player may need to repeat this level a couple of times. The next difficulty presents those same tasks in the same order, but without any hints. The last difficulty switches around the order of the tasks, meaning that the player has to really know what they’re listening to before they move on to the next level! Through this process the player comes to learn and acquire language in an authentic way, and can very practically take their new language knowledge into the real world!

PROJECT TEAM:

Robert Skipper [Director]

Lucas von Hollen [Additional Design]

Jordan Kramer [Additional Project Management]

Rhett Gordon [Lead Programmer]

Logan Harrold [Programmer]

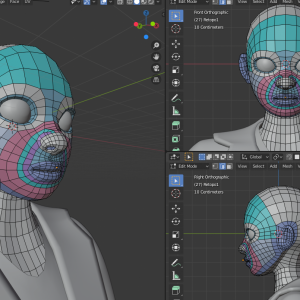

Karalynn Raya [Lead Artist]

Bryan Clark [3D Modeler]

Alexander Wood [Lead Animator]

Joel Ramirez [Character Modeler]

Taelin Farrell [Additional Models]

Breanna Smith [Additional Models]

Christian Rodriguez [Additional Models]

Christopher Tonner [Sound]